Marginal cost

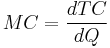

In economics and finance, marginal cost is the change in total cost that arises when the quantity produced changes by one unit. That is, it is the cost of producing one more unit of a good.[1] If the good being produced is infinitely divisible, so the size of a marginal cost will change with volume, as a non-linear and non-proportional cost function includes the following:

- variable terms dependent to volume,

- constant terms independent to volume and occurring with the respective lot size,

- jump fix cost increase or decrease dependent to steps of volume increase.

In practice the above definition of marginal cost as the change in total cost as a result of an increase in output of one unit is inconsistent with the calculation of marginal cost as MC=dTC/dQ for virtually all non-linear functions. This is as the definition MC=dTC/dQ finds the tangent to the total cost curve at the point q which assumes that costs increase at the same rate as they were at q. A new definition may be useful for marginal unit cost (MUC) using the current definition of the change in total cost as a result of an increase of one unit of output defined as: TC(q+1)-TC(q) and re-defining marginal cost to be the change in total as a result of an infinitesimally small increase in q which is consistent with its use in economic literature and can be calculated as dTC/dQ.

In general terms, marginal cost at each level of production includes any additional costs required to produce the next unit. If producing additional vehicles requires, for example, building a new factory, the marginal cost of those extra vehicles includes the cost of the new factory. In practice, the analysis is segregated into short and long-run cases, and over the longest run, all costs are marginal. At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal costs include all costs that vary with the level of production, and other costs are considered fixed costs.

If the cost function is differentiable joining, the marginal cost is the cost of the next unit produced referring to the basic volume.

If the cost function is not differentiable, the marginal cost can be expressed as follows.

A number of other factors can affect marginal cost and its applicability to real world problems. Some of these may be considered market failures. These may include information asymmetries, the presence of negative or positive externalities, transaction costs, price discrimination and others.

Contents |

Cost functions and relationship to average cost

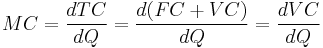

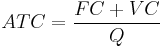

In the simplest case, the total cost function and its derivative are expressed as follows, where Q represents the production quantity, VC represents variable costs, FC represents fixed costs and TC represents total costs.

Since (by definition) fixed costs do not vary with production quantity, it drops out of the equation when it is differentiated. The important conclusion is that marginal cost is not related to fixed costs. This can be compared with average total cost or ATC, which is the total cost divided by the number of units produced and does include fixed costs.

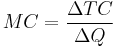

For discrete calculation without calculus, marginal cost equals the change in total (or variable) cost that comes with each additional unit produced. In contrast, incremental cost is the composition of total cost from the surrogate of contributions, where any increment is determined by the contribution of the cost factors, not necessarily by single units.

For instance, suppose the total cost of making 1 shoe is $30 and the total cost of making 2 shoes is $40. The marginal cost of producing the second shoe is $40 - $30 = $10.

Marginal cost is not the cost of producing the "next" or "last" unit. [2]As Silberberg and Suen note the cost of the last unit is the same as the cost of the first unit and every other unit. In the short run increasing production requires using more of the variable input - conventionally assumed to be labor. Adding more labor to a fixed capital stock reduces the marginal product of labor because of the diminishing marginal returns. This reduction in productivity is not limited to the additional labor needed to produce the marginal unit - the productivity of every unit of labor is reduced. Thus the costs of producing the marginal unit of output has two components: the cost associated with producing the marginal unit and the increase in average costs for all units produced due to the “damage” to the entire productive process (∂AC/∂q)q. The first component is the per unit or average cost. The second unit is the small increase in costs due to the law of diminishing marginal returns which increases the costs of all units of sold.[1] Therefore, the precise formula is:

MC = AC + (∂AC/∂q)q.

Marginal costs can also be expressed as the cost per unit of labor divided by the marginal product of labor. [3]

- MC = ∆VC∕∆q;

- ∆VC = w∆L;

- MC = w∆L;/∆q;

- ∆L∕∆q the change in quantity of labor to affect a one unit change in output = 1∕MPL.

- Therefore MC = w/MPL [4]Since the wage rate is assumed constant marginal cost and marginal product of labor have an inverse relationship - if marginal cost is increasing (decreasing) the marginal product of labor is decreasing (increasing).[5]

Economies of scale

Economies of scale is a concept that applies to the long run, a span of time in which all inputs can be varied by the firm so that there are no fixed inputs or fixed costs. Production may be subject to economies of scale (or diseconomies of scale). Economies of scale are said to exist if an additional unit of output can be produced for less than the average of all previous units— that is, if long-run marginal cost is below long-run average cost, so the latter is falling. Conversely, there may be levels of production where marginal cost is higher than average cost, and average cost is an increasing function of output. For this generic case, minimum average cost occurs at the point where average cost and marginal cost are equal (when plotted, the marginal cost curve intersects the average cost curve from below); this point will not be at the minimum for marginal cost if fixed costs are greater than zero.

Perfectly competitive supply curve

The portion of the marginal cost curve above its intersection with the average variable cost curve is the supply curve for a firm operating in a perfectly competitive market. (the portion of the MC curve below its intersection with the AVC curve is not part of the supply curve because a firm would not operate at price below the shut down point) This is not true for firms operating in other market structures. For example, while a monopoly "has" an MC curve it does not have a supply curve. In a perfectly competitive market, a supply curve shows the quantity a seller's willing and able to supply at each price - for each price there is a unique quantity that would be supplied. The one-to-one relationship simply is absent in the case of a monopoly. With a monopoly there could be an infinite number of prices associated with a given quantity. It all depends on the shape and position of the demand curve and its accompanying marginal revenue curve.

Decisions taken based on marginal costs

Firms decide the quantity to be produced based on marginal costs and sale price. If the sale price is higher than the marginal cost, then they supply the unit and sell it. If the marginal cost is higher than the price, it would not be profitable to produce it. So the production will be carried out until the marginal cost is equal to the sale price. In other words, firms refuse to sell if the marginal cost is higher than the market price. [6]

Relationship to fixed costs

Marginal Costs are not affected by changes in fixed cost. Marginal costs can be expressed as ∆C(q)∕∆Q. Since fixed costs do not vary with (depend on) changes in quantity, MC is ∆VC∕∆Q. Thus if fixed cost were to double MC would not be affected and consequently the profit maximizing quantity and price would not change. This can be illustrated by graphing the short run total cost curve and the short run variable cost curve. The shape of the curves are identical. Each curve initially increases at a decreasing rate, reaches an inflection point, then increases at a decreasing rate. The only difference between the curves is that the SRVC curve begins from the origin while the SRTC curve originates on the y-axis. The distance of the origin of the SRTC above the origin represents the fixed cost - the vertical distance between the curves. This distance remains constant as the quantity produced, Q, increases. MC is the slope of the SRVC curve. A change in fixed cost would be reflected by a change in the vertical distance between the SRTC and SRVC curve. Any such change would have no effect on the shape of the SRVC curve and therefore its slope at any point - MC.

Externalities

Externalities are costs (or benefits) that are not borne by the parties to the economic transaction. A producer may, for example, pollute the environment, and others may bear those costs. A consumer may consume a good which produces benefits for society, such as education; because the individual does not receive all of the benefits, he may consume less than efficiency would suggest. Alternatively, an individual may be a smoker or alcoholic and impose costs on others. In these cases, production or consumption of the good in question may differ from the optimum level.

Negative externalities of production

Much of the time, private and social costs do not diverge from one another, but at times social costs may be either greater or less than private costs. When marginal social costs of production are greater than that of the private cost function, we see the occurrence of a negative externality of production. Productive processes that result in pollution are a textbook example of production that creates negative externalities.

Such externalities are a result of firms externalising their costs onto a third party in order to reduce their own total cost. As a result of externalising such costs we see that members of society will be negatively affected by such behavior of the firm. In this case, we see that an increased cost of production on society creates a social cost curve that depicts a greater cost than the private cost curve.

In an equilibrium , state we see that markets creating negative externalities of production will overproduce that good. As a result, the socially optimal production level would be lower than that observed.

Positive externalities of production

When marginal social costs of production are less than that of the private cost function, we see the occurrence of a positive externality of production. Production of public goods are a textbook example of production that create positive externalities. An example of such a public good, which creates a divergence in social and private costs, includes the production of education. It is often seen that education is a positive for any whole society, as well as a positive for those directly involved in the market.

Examining the relevant diagram we see that such production creates a social cost curve that is less than that of the private curve. In an equilibrium state we see that markets creating positive externalities of production will under produce that good. As a result, the socially optimal production level would be greater than that observed.

Social costs

Of great importance in the theory of marginal cost is the distinction between the marginal private and social costs. The marginal private cost shows the cost associated to the firm in question. It is the marginal private cost that is used by business decision makers in their profit maximization goals, and by individuals in their purchasing and consumption choices. Marginal social cost is similar to private cost in that it includes the cost functions of private enterprise but also that of society as a whole, including parties that have no direct association with the private costs of production. It incorporates all negative and positive externalities, of both production and consumption.

Hence, when deciding whether or how much to buy, buyers take account of the cost to society of their actions if private and social marginal cost coincide. The equality of price with social marginal cost, by aligning the interest of the buyer with the interest of the community as a whole is a necessary condition for economically efficient resource allocation.

See also

- Cost

- Cost curve

- Average cost

- Economic surplus

- Marginal concepts

- Marginal revenue

- Marginal product of labor

- Externality

- Merit goods

- Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis

- Break even analysis

References

- ^ Sullivan, arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). [TC Economics: Principles in action]. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 111. ISBN 0-13-063085-3. TC.

- ^ Silberberg & Suen, The Structure of Economics, A Mathematical Analysis 3rd ed. (McGraw-Hill 2001) at 181.

- ^ See http://ocw.mit.edu/NR/rdonlyres/Economics/14-01Fall-2007/F4843AF1-1F54-46B5-A2BA-AE728225F274/0/14_01_lec13.pdf.

- ^ Chia-Hui Chen, course materials for 14.01 Principles of Microeconomics, Fall 2007. MIT OpenCourseWare (http://ocw.mit.edu), Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Downloaded on [12 Sept 2009].

- ^ Note also that AVC = VC/Q=wL/Q = w/(Q/L) OR w/APL

- ^ "Piana V. (2011), Refusal to sell - a key concept in Economics and Management, Economics Web Institute."

|

||||||||